Between 2000–2002, my apprenticeship with Ignacio Ulloa revealed the foresight of power at odds with my university’s teachings on economics. Ignacio embodied a ruthless clarity: money was a tool, power the real prize. His crusade against Galicia’s political classes exposed a bureaucracy unfit for crises like the Prestige oil spill, yet his technocratic solution -competence without conscience- haunted me. Nietzsche’s question, “free for what?” became my own. Ignacio showed me the force of nihilism: power for its own sake. But my passion for technique, for craft and mastery, kept me from drowning in that abyss. From this tension sprouted the first seeds of the Fondo Natural project.

Rearview Economics vs. the Foresight of Power

Between 2000 and 2002, while Ignacio Ulloa exposed me to his living embodiment of power in the corporate and financial world, I was also taking several economics courses as part of my industrial engineering studies in Vigo, Spain. These courses were: Teoría e Instituciones Económicas (Theory and Economic Institutions), Administración de Empresas (financial accounting), Teoría Económica de la Empresa (Economic Theory of Corporations), Investigación Operativa (Operational/Logistics research) and Mercados (Marketing).

On paper, such an academic foundation should have made it easier for me to uncover the true sources of richness. Yet what bothered me most was realizing that Ignacio -who had no real theoretical training in economics- was able to make multimillion-euro commissions from corporate operations that generated genuine techno-industrial value. He may not have been “rich” in the sense I employ the term in these articles, but he pursued power in ways that were utterly inconceivable to my professors.

Due to the combination of Ignacio´s mysterious origins and his ideas being so far ahead -more evolved, more practical, more powerful- than anything I encountered in public opinion or in the academic ivory tower, I sometimes found myself crazily wondering if Ignacio Ulloa had traveled back from the future in a time machine. His visionary traits seemed less like eccentric genius than the result of always betting on the winning horse in history, of practicing what Aristotle once defined as true politics: the art of the possible.

Under Ignacio’s powerful influence, I began to suspect that something essential was missing everywhere, as if the entire world were slightly off balance. By 2001, I was already sensing that what I was being taught at university was only a shadow of a greater light, a retrospective vision of economics -like driving while staring only at the rearview mirror- whereas Ignacio’s way of acting seemed to anticipate what lay ahead. His ruthless coherence between thought and action stood in sharp contrast to the sterile academic detachment that filled the student circles around me. Through him, I began to perceive the hidden architecture linking wealth, money, and human identity; layers of abstraction that most people never even glimpse.

That realization plunged me into a kind of lucid nihilism: a deep, ironic disbelief in every conventional form of “success” within the economic sphere. It was then that I understood why Ignacio was so widely feared: his mere presence was enough to shatter the most cherished human ideals. I admired his brutal honesty, but that admiration soon turned into a kind of exile. By 2001–2002, I could barely stomach the sight of how entire careers and academic institutions had surrendered themselves to the cold abstraction of economics. The hypocrisy of it all infuriated me; the way living minds bowed before dead numbers. The words of the character played by Mark Wahlberg in the following clip could´ve been perfectly mine during those years:

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering

Yet that same disbelief compelled me to search for something real, something that held true value. And whatever one might think of Ignacio’s personal ethics, his actions in the economic realm were authentic and substantial, a precise projection of his worldview and his understanding of human nature.

Due to Ignacio´s personal example I became one of the very few in my faculty to notice that most of our engineering curriculum treated machines, devices, and technical systems as givens. We were trained to analyze their forms, measure their properties, simulate their dynamics and apply reductionist models, but not to understand the living, dynamic processes that brought them into being. My father’s ancestors had been artisans and blacksmiths deeply linked to the land. so I knew firsthand that there’s a world of difference between describing the geometry of a horseshoe and mastering the operative craft required to forge it. Ignacio, by contrast, was engaged precisely in those creative processes of corporate genesis -where added value is born- while my courses at the university described static snapshots, drained of creative potential.

Fascinated by these contrasts, I began devoting more time to Ignacio’s businesses than to the classroom. What struck me most was that he made enormous sums of money without even desiring it, as if he embodied the Eastern notion of wei wu wei, “action without action,” but transposed into the economic domain.

These years of apprenticeship also coincided with Spain’s transition from the peseta to the euro. Ignacio interpreted it not as a monetary adjustment, but as a profound shift in the values of the Spanish people and the new generations. In my novel The Soul of the Sea, I describe how his vision on economics seeped into my psyche, infecting me with a way of thinking about economics as part of a larger entelechy he always called the Zeitgeist, a force that reshapes the very architecture of reality.

In the following video I created in 2015 can be glimpsed some first approaches to such powerful idea:

However, during my period as an engineering student I could only grasp intuitively all this creative force. It wasn’t until 2006, when I re-read Ernst Jünger’s Der Arbeiter with renovated eyes, that I realized Jünger had perceived the same phenomenon and named it with precision: technique. And technique, as I shall keep exploring in these articles, is not the same as “technology”.

Already before the 1950s, Lionel Robbins of the London School of Economics had warned of this confusion:

“At the present day, one of the main dangers to civilization arises from the inability of minds trained in the natural sciences to perceive the difference between the economic and the technical.” (Kenneth E. Boulding, Is Economics Necessary? Scientific Monthly, 1949)

Looking back, even my training as an industrial engineer would have been entirely insufficient to perceive the power of technique over economics, if not for the example Ignacio Ulloa set for me in those decisive years.

Oil, Water, and the Burden of Power

The existential experiences I narrate in The Soul of the Sea, combined with the catastrophic ecological destruction caused by the Prestige oil spill in 2002, forced me to radically reconsider my values and personal goals. That disaster revealed not only the technical incompetence of the Xunta de Galicia and the central government of Spain, but also the violent clash between frenetic techno-industrial development and Galicia’s ancient, almost sacred, bond with the land. The results were ecologically, socially and spiritually devastating.

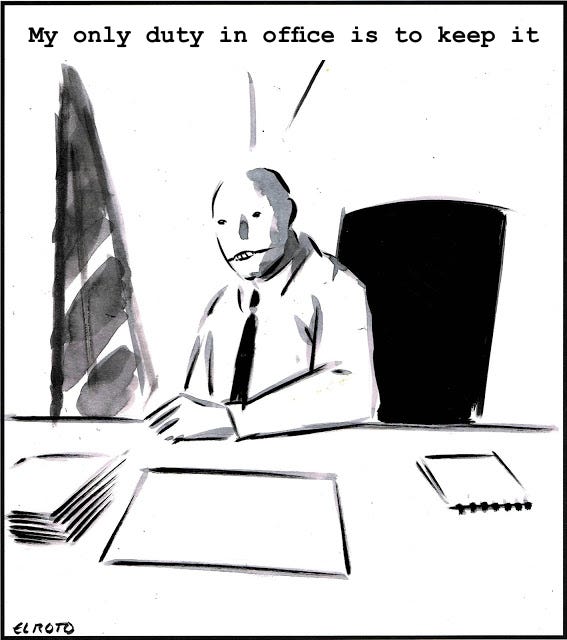

At the same time, my apprenticeship under Ignacio Ulloa (2000–2002) had already exposed me to another unsettling truth: the administrators in charge of Galicia’s institutions were not technocrats, not problem-solvers, but bureaucrats. They hid behind paperwork and computer screens, blind to the real processes unfolding beyond them. Ignacio often railed against what he called the castuza -the entrenched political caste- and the delfines, those dynastic scions born into positions of political influence regardless of merit, skill, or character. To him, they embodied Galicia’s worst vice: political decadence in the borrowed robes of prestige.

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering

Ignacio’s solution was simple and ruthless: replace them with disciplined, competent, almost military technocrats, like the engineers and planners mobilized in the U.S. and U.K. during the world wars. He believed only this could prevent further disasters like the Prestige or the Mar Egeo wreck off the Tower of Hercules in 1993. And I knew he was grooming me for that future. He made it clear that once I had accumulated enough experience and merit under his guidance, he would position me in a high-echelon technocratic role, perhaps even at the European level.

But the more I reflected on all this, the more troubled I became. What was the point of consolidating technocratic power if we could not answer the deeper question: power for what?... Without that answer, technocracy itself risked becoming a machine that devoured the human spirit. Every time I raised this doubt with Ignacio, I could sense his discomfort, almost a flicker of guilt. It was the unspoken boundary in our conversations. Oil and water do not mix, and neither did our values.

It was during this inner split that Nietzsche’s words in Thus Spoke Zarathustra began to haunt me, even in nightmares:

“Do you call yourself free? I want to hear your ruling idea, not that you have escaped a yoke… Free from what? Zarathustra does not care about that! But free for what?”

For me, this was the terrifying realization of nihilism. Ignacio embodied it perfectly. He believed human morality had no basis left, no practical value, and that power for the sake of power was the ultimate task a man had to undertake. In many respects, I could not deny he was right. It made me look at those around me as if they were playing videogames with their own lives, sleepwalking through appearances.

And yet, I could not allow myself to sink completely into that darkness. My teenage passion for mastering technique -for shaping my body, for uncovering the values hidden in craft- refused to let me drown. I needed to believe that power could be poured into something higher, that it could serve the fullest potentials of the human condition. That fragile conviction was what kept me from vanishing into the abyss.

As Scripture says, ‘Unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit’ (John 12:24). So it was with me. Like a seed buried in dead soil, I soon discovered the sources of richness that could offer a human justification for power and wealth. Those sources became the first seeds of the Fondo Natural project, which I will address in more detail in the following articles.

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering