In this article I describe how at nine, moving from London to rural Galicia left me with a fracture: my body in Spain, my mind still in Britain. That cultural exile became my first classroom in economics. London had taught me money was destiny, yet Galicia revealed something older: barter rooted in honor, production as an expression of being, money treated with suspicion. These contradictions shaped my earliest insights into the moral and spiritual nature of economics. By my teens I realized books and classes promising “economic science” offered little substance. Real lessons came from lived contrasts: a father’s restaurant struggling despite being the largest in town, rural elders who valued loyalty over solvency, and later, the paradoxical worlds of consumerism, drug networks, and business mentors like Ignacio Ulloa. From Monopoly boards to Nietzsche’s Will to Power, these years taught me that the real question is not how people make money, but how they use it, and whether it becomes richness or emptiness.

* * *

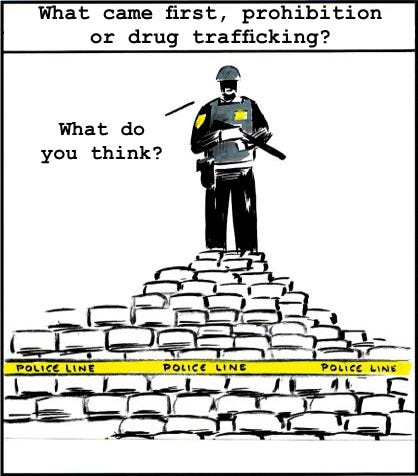

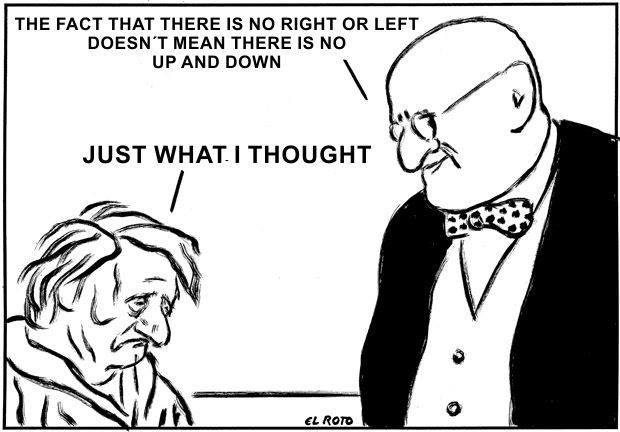

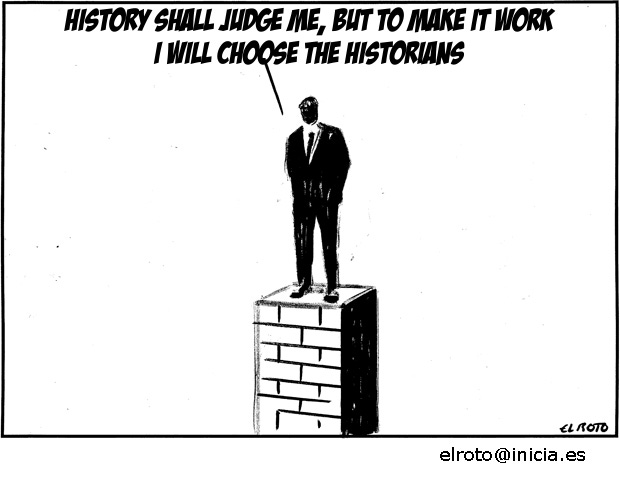

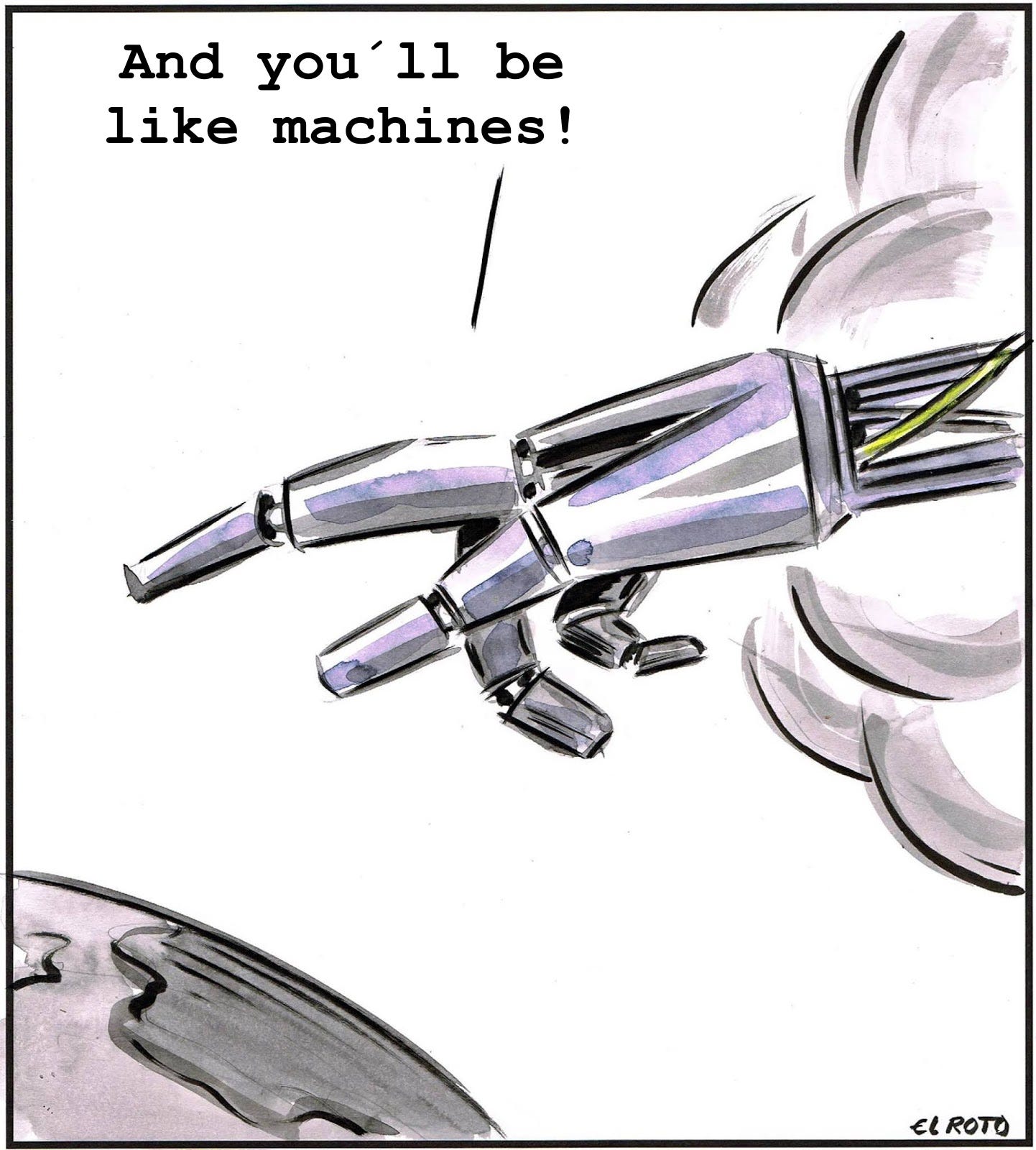

Along these articles I include many cartoons from diverse sources, (i.e. El Roto, etc.) because as Nietzsche already pointed out: “I know best why man alone laughs: he alone suffers so deeply that he had to invent laughter. The unhappiest and most melancholy animal is, as fitting, the most cheerful” (Will To Power, 91)

* * *

An Alien on Earth: My First Lessons on Money

One of the events that shaped my entire life was moving from London to Galicia in 1986. I had adapted well to British education, had close friends, and dreamed of becoming a Boy Scout. At 8, starting over in Spain felt like being exiled. Like many immigrant families, my parents worked abroad to save money with the hope of returning wealthier. But my mother and I had already absorbed British standards, and leaving felt like betrayal.

In Spain, I carried a “split” inside me: my body in Galicia, my mind still in Britain. This fracture gave me a unique vantage point; it allowed me to contextualize at a very early age the contrasts that not only exist in terms of culture but also in terms of economics. What´s more, it was just a matter of little time that I discovered that both domains are intimately connected.

London pulsed with frenetic economic life, while Galicia, then modernizing its public sector, was full of workers chasing the middle-class comforts my family had already left behind. I couldn’t share that ambition. Why repeat what we’d already abandoned?... It wasn´t that I didn´t understand the rules of `Monopoly´ at an early age or either the business advantages of getting in debt with banks; it´s that I became poorly motivated by the drive towards pursuing bigger and bigger things. Whereas in London I made friends by playing fighting games with a core sense of comradeship, in Galicia friends were built based on very superficial aspects (clothing brands, etc.) I couldn´t relate to. So I lived as a foreigner, preferring solitude and sincerity over the vanity of clothing brands and shallow friendships.

The Galicia of the 1990s was still a hybrid between industrial development and rural traditions, and yet this tension fascinated me. My father´s family is native to the area of the Courel mountain range, in a town that´s rooted about thousand years back in its natural conditions. The cultural heritage of its elders still presented in the 1990s some traditional aspects that bewildered me, especially by considering that these aspects completely contradicted the worldviews I had imported from London. They shared with me stories of pre–Civil War barter systems where “credit” meant personal honor, not bank solvency. A man’s word was worth more than his coin. Money was viewed with suspicion, while loyalty, reputation, and barter preserved both freedom and survival. These “prehistoric” memories disconcerted me, but I sensed their depth. They revealed an economy grounded in spiritual relations -with the land, with craft, with community- that had sustained autonomy for centuries. By contrast, London had taught me that money was destiny. Nothing -art, culture, sport, knowledge- could thrive over there without being monetized.

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering

Rural Galicia revealed another truth: that economic life could be framed by spiritual values, not just profit. It was jarring to see the last artisans of the town refuse tractors or families walk instead of driving, even if they perfectly had the technical skills, knowledge, work experience and community support required to profit from such techniques. I couldn’t make sense of it as a teenager, but I intuited that money carried religious undertones, sometimes guiding, sometimes corrupting. These first insights on the spiritual nature of economics were like seeds planted in me, long before I acquired the conceptual frameworks to grasp them.

The Restaurant That Taught Me Economics

Already at twelve, I couldn’t understand how my father could own the largest restaurant in town and still struggle to cover our family’s needs. For the first time, the contrast between “wealth” and “money in hand” hit me directly. I assumed it was an economic puzzle, so I dived into the marketing manuals and flashy concepts being taught in the same academies that had just begun offering computer courses. Still naively clinging to the idea that books could explain everything, I devoured titles like How to Make More Money, etc. My friend Emilio cut through the illusion with a single joke: “The only ones who get more money from those books are their authors!” He was right. Those early disappointments shifted my attention.

But within a year, I realized the problem wasn’t economic at all. It was cultural. Restaurant culture in London was not the same as in Spain, and my father’s business was caught in that clash. I began to see that if you solved the cultural issues, the economic ones would fall into place almost naturally. Money was the symptom, not the cause.

Though my parents spent their entire lives working in the demanding hospitality sector, I came to realize that this field holds economic lessons that no classroom can easily capture. It’s not that an MBA is irrelevant -it provides useful frameworks and models- but certain truths about risk, resilience, human behavior, and survival in a tough market can only be learned in the heat of daily practice with customers of very diverse backgrounds. This outlook often made people assume I “despised” economics, MBAs or was indifferent to how people earned their living. In truth, I was simply more fascinated by the values behind their choices than by the balance of their bank accounts.

At sixteen, I enrolled in my first economics class at high school. By then, I had already begun to sense the deep ties between culture and economics. Not just between “situations” in each field, but between the underlying values that shape them both. To me, it’s far more revealing to watch how someone handles a mortgage problem than to know whether that mortgage is for a mansion or a modest flat.

Naively, I believed the class would clarify things, just as I once believed high school itself would make me intelligent. Instead, the course promised “science” but delivered little more than abstractions. I didn’t care much about Adam Smith, Marx, or Ricardo; I wanted practical tools: how to file taxes to help my parents, how to run accounts on a spreadsheet. None of that was taught. I passed the exams, but was left with nothing of substance. Until my 20s I didn´t realize that to call economics a science is misleading; it’s a set of techniques that derive from our personal values.

Lessons Greed Can´t Buy

Meanwhile, during my teens, Galicia’s new middle class was plunging into consumerism, chasing credit cards and comforts that seemed hollow compared to the rural wisdom I was hearing from elders. Between London’s monetized destiny and Galicia’s spiritual resistance, I grew up feeling like an alien on earth, bewildered, yet sharpened by the clash.

On one hand, rural Galicia still carried the conviction that how we produce is an expression of who we are. On the other, the new urban Galicia of the 1990s was racing headlong into consumerism and entertainment, where the act of buying seemed to matter more than the art of making. At the same time, the region itself was being reshaped: industry relocated to central Europe and Asia, rural areas emptied out, ancestral traditions withered.

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering

Amid this upheaval, I found myself strangely bewitched by the arts of production. That fascination -rather than any hunger for consumption- was what drew me to industrial engineering, which I saw as a first apprenticeship in the craft of making. Yet this passion for production set me apart.

This sense of estrangement often brought back an old memory: as a child, I never liked sweets, even chocolates. Other kids devoured them with joy; I would refuse them, powerless to explain why. That early refusal somehow foreshadowed my later resistance to the sugary temptations of consumerism. My complete lack of greed made me seem odd, even defective, to those around me. Greed was so quickly becoming normalized that I often felt like a fish out of water, or worse, guilty for not swimming with the current.

Still feeling like a fish out of water when it came to my economic motivations, in 1999 I failed to convince my father to let me continue my second cycle of industrial engineering in Germany, despite having a personal recommendation from Mariano Pérez Amor, full professor of physics at the University of Vigo. The obstacle I encountered wasn’t financial, it was cultural. Once again, I was confronted with the fact that cultural values run deeper than economic ones.

So I stayed in Galicia and tried to make the most of my situation. After 1999 my main struggle wasn’t academic or financial; it was existential. Even considering I was quite a good student, I simply couldn’t find any genuine economic or career-driven motivation to continue in industrial engineering. Most of my classmates had no such doubts: the prospect of high salaries and social prestige was enough to keep them on track, especially compared to the uncertain future of many liberal professions. In Spain, they say envy is the national sport (“la envidia es el deporte nacional”), and by then greed and envy had become normalized as almost respectable ambitions. Yet I was strangely immune to both.

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering

My path felt different. Shaped by the experiential knowledge I’d carried since the age of 9, and by the cultural clash that still gnawed at me from within, I could only see money and engineering as means, never as ends. But that left me with a deeper problem: if they were means, then means to what?... My family couldn’t answer. My professors couldn’t answer. I longed for a guide, some mentor who could help me translate my lived experience into realistic goals, goals that would fit the knowledge I had already painfully earned on my own.

After 1999 a mix of frustration and adventurous spirit pushed me well beyond the classroom. It was during this time that I met Ignacio Ulloa, who would later become one of the key characters in my first novel, The Soul of the Sea. Ignacio gave me teachings on economics that no textbook ever could, lessons that stayed with me and became the foundation for the Fondo Natural project, which I would go on to develop from scratch only three years later.

Power Beyond Greed and Morals

In the so-called information age, people pride themselves on having an answer for everything. But when I was twenty, my head was still crowded with questions, and the university education I was receiving back then offered very few answers. What I discovered, however, was that if I kept the questions alive, they seemed to “magnetize” answers in unexpected ways. For me, one of the most decisive answers came embodied in the unlikely figure of a businessman, Ignacio Ulloa. But before our paths crossed, I had to walk through a troubling landscape of moral contradictions.

During the 90s it was still possible to listen some people make use of an insulting term “Mamón” (mammon, Aramaic: מָמוֹנָא, māmōnā) which in the New Testament is commonly conceived as any personification or divinization of greed. And yet it´s been about 20 years that I haven´t heard anyone employ the term “Mamón” any longer, and this is due to the normalization of greed.

Greed and envy weren’t just tolerated, they were practically canonized. To resist them felt almost heretical, as if I were defying a new global religion. The words of Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas) in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987) echoed through the corridors of business schools and student bars: “Greed, for lack of a better word, is good.” And if Gekko had gone one step further and declared “Greed is God,” he wouldn’t have been far off. After all, greed is what religion literally means in its Latin root: re-ligare, the binding force that unites a people.

In the film, Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen) tells his father (Martin Sheen) that “there is no nobility in poverty”. It was not just a line from a script, it was the creed of my generation. You could hear echoes of it everywhere: “They must be good at it, they get paid well”. Hidden inside that casual phrase was a dangerous assumption: that money itself is the final authority, the ultimate justification of anything.

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering

The Moral Paradox of Work

But my own conscience was already troubled. By then, I was studying just a stone’s throw from one of Europe’s major drug-trafficking networks. Behind the façade of small companies with harmless names like “Industrial Supplies and Maintenance” it was an open secret that sophisticated cocaine logistics were driving their suspicious profits. The contrast was too obvious: the companies showed impressive margins, yet their staff had shockingly poor technical skills. Their real business was outsourced, and their true expertise was contraband.

For a young engineering student like me, the temptation was real. These networks offered something that both fascinated and unsettled me: they paid more for loyalty more than greed. In fact, greed was the one flaw they couldn’t afford because a greedy man was a man who could be blackmailed, bribed, or broken. So they looked instead for reliability: people clean from drugs, trustworthy, committed. In this paradoxical way, the “illegal” world placed far greater emphasis on honor, loyalty, and personal reliability than the “legal” corporate world around me, where employees would jump ship for the smallest raise in the rat race, abandoning apprenticeships and commitments without a second thought.

That inversion gnawed at me. On paper, the “legal” world was moral and the “illegal” world corrupt. But in lived experience, it often felt the other way around. The only money I had was earmarked for tuition. In academia, my character, reliability, and creativity meant nothing; what counted was grinding through exams in a bureaucratic system where self-respect had no place and true authority was faceless, abstract. Meanwhile, in the “illegal” world, young guys like me capable of cold technical reasoning, but fiercely loyal once trust was given, were valued, respected, even sought after.

From a young age, my immunity to cynicism and hypocrisy became less a virtue than a burden of conscience. It made me painfully sensitive to the fragile moralism attached to certain professions -those labeled “decent” or “honorable”- as if their dignity were inherent, rather than circumstantial. My broader, colder view of things quickly revealed the relativity behind such labels.

For instance, in late 1990s Spain police recruitment surged. To join the police was considered “good,” even noble. Yet their jobs only existed because thieves and criminals existed too. The institution required crime to perpetuate itself and justify its budgets. Were officers still “good” in a system that depended on the “bad”?...

Drug traffickers were condemned as villains, yet what were they doing, in essence, that differed radically from pharmaceutical giants?... Cocaine may destroy lives, but legal antidepressants rarely cure -only manage symptoms- while keeping profits flowing. One sells powder in alleys, the other sells pills in pharmacies; society crowns one with prestige and demonizes the other.

Politicians, too, thrive not on truth but on demagoguery, the exploitation of mass credulity. Professors, clinging to their title, rarely aim to liberate thought; most depend on students who prefer shortcuts and to genuine ethical discipline. In fact, in Spain the most institutionalized ones are often ashamed of being called “teachers” and they prefer to be called “docentes”, as if it sounds more decent than the term “teachers”. Lawyers, admired as guardians of order, are indispensable only where social trust has already collapsed. A cohesive community bound by shared values, loyalty and trust barely needs them. And medical doctors -icons of prestige- only exist because sickness exists. Without illness, their profession disappears.

The paradox is striking: those who consider themselves “good” cannot function without the very “bad” they define themselves against. Which came first: the healer or the sick, the cop or the criminal?... It’s a chicken-and-egg dilemma buried in the structure of modern work.

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering

As Jacques Ellul observed, in technical professions -engineering, electricians, mechanics, plumbing, etc.- the most efficient technician is the one who does not entangle his trade with moral posturing. The work speaks for itself: the bridge stands, the machine runs, the light turns on. Honest in its independence from society’s shifting judgments.

And yet, even here, my dilemma persisted. Though engineering well fit my work standards, I did not want to abandon my human sensitivity and become just another cog in a technical system. So I stood before the question that haunted me at twenty: How can one find work that is both honest -independent of circumstantial morality- and yet still preserves, even matures, one’s human sensitivity?...

It was this moral dissonance, this clash between appearances and lived truths, that eventually led me to Ignacio Ulloa, a man who, outside the classroom, would become one of my most unusual and influential teachers.

Ignacio Ulloa: The Teacher Outside the Classroom

At twenty, I felt morally adrift. I was stuck between paths -one legal, one illegal- and Ignacio Ulloa became the force that pushed me forward. Looking back, I can’t see our meeting in a café-bar in Vigo as mere coincidence. Even in our first small-talk exchanges, it was clear we shared a visceral rejection of cynicism, cowardice, vanity, pretentiousness, organized religion, petit-bourgeoisie conformism and shallow self-interest. That rejection sat at the core of his character, though he camouflaged it so well that universities occasionally invited him to lecture, despite his utter contempt for academia.

Ignacio was a mystery. His father was Cuban, his mother from Pontevedra, and he spent his formative years overseas before returning to Galicia as an adult. Whatever the roots of his character, his vision of economics shocked me. Trained in sales since his teens he neither embraced capitalism nor communism, but something outside both. To me at the time, this was incomprehensible. But as I watched him operate -introducing me to his networks, his methods- I discovered that money wasn’t his true objective. Yes, he made a lot of it, but profit was only a by-product. His real pursuit was power.

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering

In some ways, Ignacio resembled Gordon Gekko: charismatic, strategic, feared. But unlike Gekko, he seemed immune to greed. He didn’t worship money; he treated it as a tool, as fuel for a much larger machine. For Ignacio, business was war. He radiated the presence of a statesman or a general, convinced his mission was to dismantle Galicia’s smallholding corporate culture and Spain’s decaying political structures, replacing them with something far more consolidated and relentless.

Ignacio didn’t think in terms of entrepreneurs or start-ups, he dismissed them as distractions. He thought in terms of the State; not as Spanish, French or Italian national governments, but a new, omnipresent State of power that was steadily taking hold of human life across the planet. He called its driving force the Zeitgeist; the spirit of the times. Everyone, he argued, was impelled by this force, consciously or unconsciously. Morality, he said, was a relic of pseudo-religion, a burden that had no weight against the momentum of the Zeitgeist. The only valid loyalty was to whatever proved itself powerful, whatever proved true to itself. “Only by relating to power”, he told me, “can we discover who we really are. Everything else is a waste of precious life time”. Ignacio Ulloa also liked Guns N’ Roses, though for him the guns outshone the roses every time.

His vision was, for me, both shocking and redeeming. It erased the moral dilemmas that had plagued me, showing me that greed was just one more emotion swept into the larger architecture of the State. To Ignacio, greedy people were second-class, cannon fodder for greater designs. “Whatever they claim they want or think they want” he once told me bluntly, “they all need to be slaves. And if they need to be slaves of money that’s what I give them”. He didn’t say it as cruelty but as clarity. He believed he was forcing society to glimpse its chains, and perhaps, in that shock, to awaken.

Ignacio’s genius was his ability to detect what people truly needed beneath what they claimed. Politicians, bankers, executives, celebrities, professors; they were all consumers in his eyes. Words were façades; needs revealed themselves in action. He often sounded grandiose: “In three centuries, nobody will remember Steve Jobs or Bill Gates. All they do is talk. History shall remember me”.

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering

But Ignacio´s ambition was not to stand on magazine covers or be the forefront of lobbies and industrial interests. Unlike film character Gekko, who gutted companies for profit, Ignacio specialized in integration. He orchestrated consolidations with surgical precision, like Henkel’s takeover of the La Toja soap factory in Galicia (narrated in The Soul of the Sea). During those years Hollywood had popularized the concept of “men in black” –as secret government agents or Powers that Be- but the modus operandi of Ignacio Ulloa completely revolutionized the concept in my mind. He was the most catalytic factor in techno-industrial development I ever saw: alone, like a small fish that struck fast, he moved faster than governments. For him, the real game was centralization; of capital, of information, of power.

He had no illusions about the human cost. Layoffs, broken families, ruined careers, he accepted them all as inevitable. Ignacio often said that the only way to stop a gangrene from consuming the whole body was a clean cut. In his view, the decisive cuts he carried out in the corporate world -though harsh in the moment- were, in the long run, the least painful. “If I don’t do it, someone else will” -he told me in 2001. At the time I thought him ruthless. Later, I understood his words as prophetic. “If they’re not ashamed of being sheep, why should I be ashamed of being a vulture? I’m just cleaning the mess of their corruption. People ought to thank me for this” –he once said.

Some in his circle called him a sociopath. I never agreed. He was too empathic, too capable of irony and melancholy. He often spoke of society as a marketplace of gullible prostitutes and mercenaries, and this vision clearly weighed on him. But he believed his work redeemed him: by channeling capital towards the development of the impending State, by centralizing power, he was pushing humanity beyond its hypocrisy. “If their dream is to become machines, great” -he would say. “At least machines aren’t hypocrites”.

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering

Between Greed and Greatness

Ignacio was the first person I met who drew a sharp line between money, wealth, and power. That distinction changed everything for me. After knowing him, I stopped attaching any automatic moral value -positive or negative- to money-making itself. Banker or real-estate agent, journalist or teacher, cocaine dealer or gambler; the question was no longer how people made money, but how they consumed it.

Ignacio’s teachings also forced me to rethink the work of so-called liberal professionals -teachers, doctors, administrators, lawyers- those who proudly claim to serve “with honor and public duty”. He argued, and I soon saw it too, that much of their labor no longer strengthens moral virtue, ethics, or independent thought. Instead, whether they admit it or not, their work funnels individuals into the rhythms of a society that prizes consumption over production, conformity over personal development. Seen this entire economic machinery from a wide enough angle, the old moral boundary between “decent” jobs and “indecent” ones dissolves. Both serve the same machine -one oils the gears politely, the other more crudely- but the direction of motion remains the same.

This shift made particular sense in Galicia, where the region’s natural wealth and primary industries were increasingly neglected by the Xunta regional government, while politics poured public expenditure into multiplying distribution channels and consumer outlets. In global cities like London this consumerist logic feels invisible, as if it’s just part of the air. But Galicia’s late arrival to industrialization, combined with Ignacio’s lens, let me see the fault lines more clearly.

And the moral pretenses began to blur. Whether a decorated PhD or a street sweeper dismissed by society, if both spend their evenings glued to two hours of sensationalist TV, their effective contribution to the collective isn’t so different. The best operative traditions emphasize that excellence in work and craft still matters, of course, but Ignacio sharpened my conviction that true creation -the kind of art or labor that mirrors genuine personal development- inevitably reshapes how a person spends their leisure and, in turn, how they consume and invest their money. Also, it determines the elective affinity with friends and experiences.

In societies intensively permeated by consumerism, our deepest values are mostly revealed not in the jobs we hold or the GDP we help generate, but in the way we spend and invest both our money and time. And time has never been as expensive as today. We cast a political vote once every two or four years and flatter ourselves that it defines us. Yet every day, through what we buy, we cast a far more honest vote: not for a party, but for the person we think we are, or the one we want to become.

When Power Has No Meaning

I also learned something crucial about the economic domain by observing Ignacio’s way of life, or rather, his lack of one. He was a true workaholic, incapable of leisure or comfort. Even in our long conversations, the subject was always the same: the political and corporate structures of Galicia, and how to bend their representatives to his will. He spoke with brilliance about human motivation in relation to economics, but nothing about his own private life. It was as if he had none. His connections to regional celebrities and politicians were, by his own admission, never personal; they were simply “tools” to achieve his designs.

His relentless drive toward power radiated so strongly that in 2001 I bought Nietzsche’s Will to Power edition in Spanish, trying to make sense of the philosopher’s often contradictory ideas. What guided me through that dense text was not only Nietzsche’s words but the spirit I felt emanating from Ignacio himself. It was as if the enigmatic figure of the Übermensch (Superman) had stepped out of Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra and taken a seat across from me.

And yet, the more time I spent with him, the clearer another truth became: Ignacio embodied power in its purest expression -his spiderweb of influence extended far beyond the reach of presidents, CEOs or generals- but he lacked the ability to give power meaning. It was power for its own sake, power without a human center. This discovery marked a turning point for me. Ignacio had transcended all the petty socioeconomic determinisms that bind most lives, but he was not an embodiment of richness. He could command money and authority, but he could not pour either into elevating the human condition. And that, I realized, is the crucial difference.

Ignacio and I shared a profound mutual respect, born from one simple fact: our relationship was always honest. No sugarcoating, no posturing, no need to agree or to be liked. We simply laid out our views as they were. For me, it was a revelation to discover that I could feel deep respect -even a sense of comradeship- for someone so radically different from myself. It reminded me of the spirit of conflict-driven friendship I had once known in London, where respect was forged not in harmony but in the courage to fight with a sense of fair play.

What struck me most was Ignacio’s unapologetic authenticity. I honored him for it, and in doing so, I absorbed his experiential knowledge in a way that felt almost physical, as if his lessons were etched into my own flesh. At that age, I had still more questions than answers, so I doubt he learned much from me. But I know he appreciated that I didn’t fear him as most people did, and perhaps he valued having someone willing -almost hungry- to wrestle with his worldview. Time has only sharpened my appreciation of his insight into the nexus of humans, economics, and power.

From the year 2000 to 2002, I learned from Ignacio Ulloa lessons about the relationship between individuals and economics that many professionals never glimpse even after a lifetime in the field. Oddly, this advantage made life harder: I had to endure the pressure of people who clung to a kindergarten view of economics, and my lack of interest in the ‘rat race’ was often mistaken for lack of ambition. Yet without Ignacio’s deep insights into economics and power, I could never have built the multimillion-euro Fondo Natural project from scratch. Like a good wine, his radical theses have only grown more convincing with the years.

Our paths diverged in 2002, not out of animosity but inevitability. His way and mine were simply incompatible: faced with the same problem, we would always reach for opposite solutions. Yet the core teachings I carried from him -the ability to distinguish money, power, and wealth from the deeper sources of richness- remain priceless. They are not only a memory but a living framework I will continue to explore and unfold in the articles that follow. (Continue reading here)

GET The Solar Offer. 10 books at a 70% DISCOUNT that nobody in the book industry is offering